Words by Eli Anderson

- - -

If humans had not domesticated animals more than 12,000 years ago, we would undoubtedly look like a different species today. Doing so allowed us to settle and grow our civilizations, develop our early economies, and over many generations, even changed our physiology. It also has transformed the animals themselves, taming wild boars into pigs, wild cattle into cows, and fowl into chickens. Perhaps most profound, though, is the impact of animal domestication on the environment.

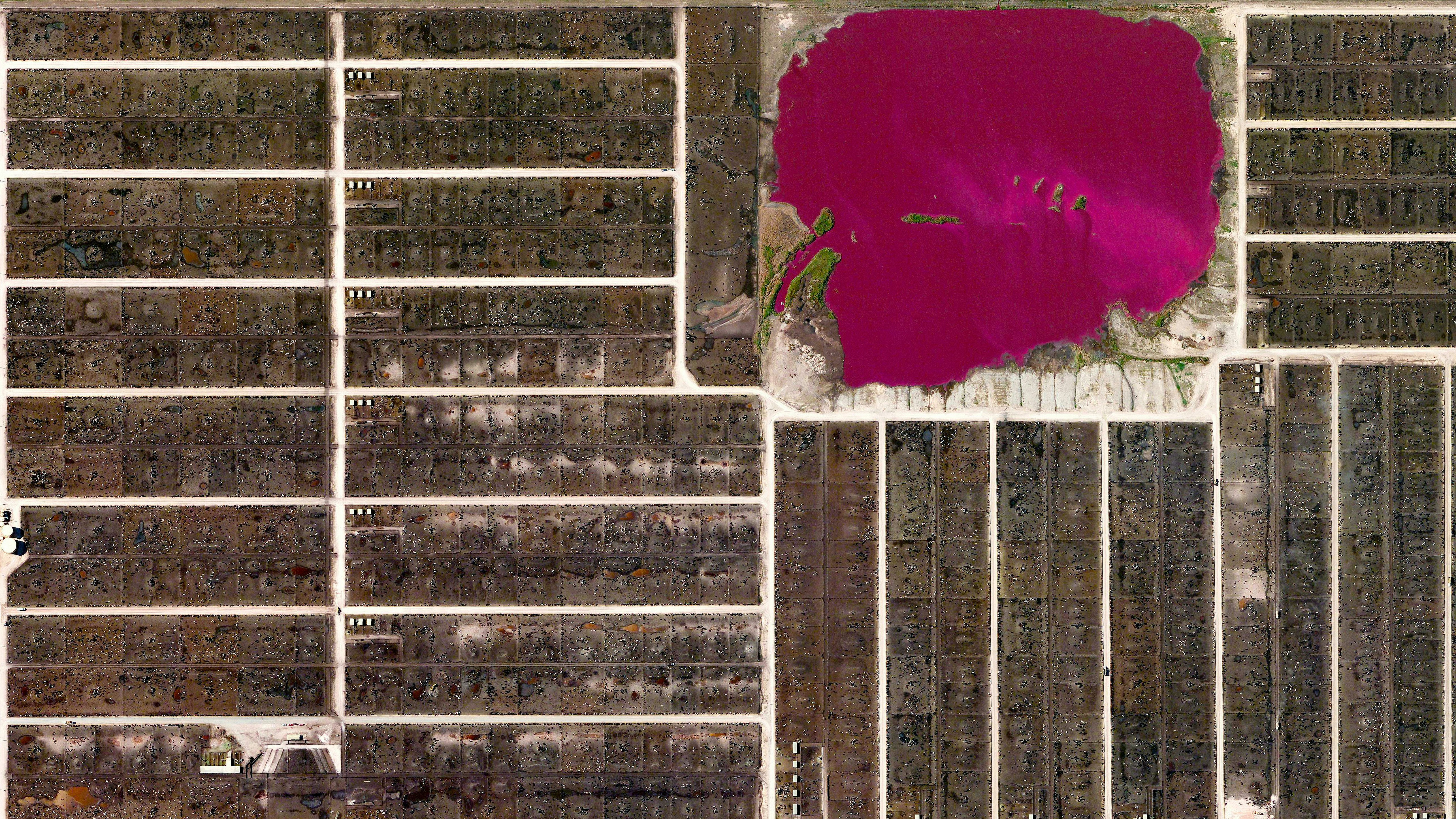

The 20th century saw massive changes in how we raise livestock, use by-products, slaughter, and consume. Decades of industrialization, animal science, and farm research have enabled us to grow larger animals, house them by the thousands, process their meat faster, cheaper, and in massive quantities. As a result, access to and demand for meat has never been greater. Earth’s human population has more than doubled in the last 50 years, but the amount of meat we produce has more than quadrupled — 355 million tons of animal meat was processed in 2018.

Today, more than 90% of Earth’s large animals are domesticated, and while some are raised as household pets or work animals, most are farmed for food. Globally, there are at least 1 billion pigs, 1 billion sheep, 1.5 billion cows, and 23 billion chickens alive, a vast majority of which are raised for slaughter on concentrated animal feed operations, or factory farms. And as demand for meat and other animal products continues to grow, expanding factory farms are tapping out Earth’s water resources, overtaking its land, and polluting the atmosphere and oceans.