Reclaiming land has its benefits. On the most basic level, it creates space—new land can be used to alleviate a congested city, construct new homes, infrastructure, and even add public parks, beaches or other open-air enhancements. In Hong Kong, a mountainous city of 7.5 million people and growing, land reclamation has been a key solution to curb overcrowding. Most of the city’s urban area is built on reclaimed land and a new development project, the “Lantau Tomorrow Vision,” plans to add 4,200 acres (1,700 hectares) of land and house as many as 1.1 million Hong Kongers.

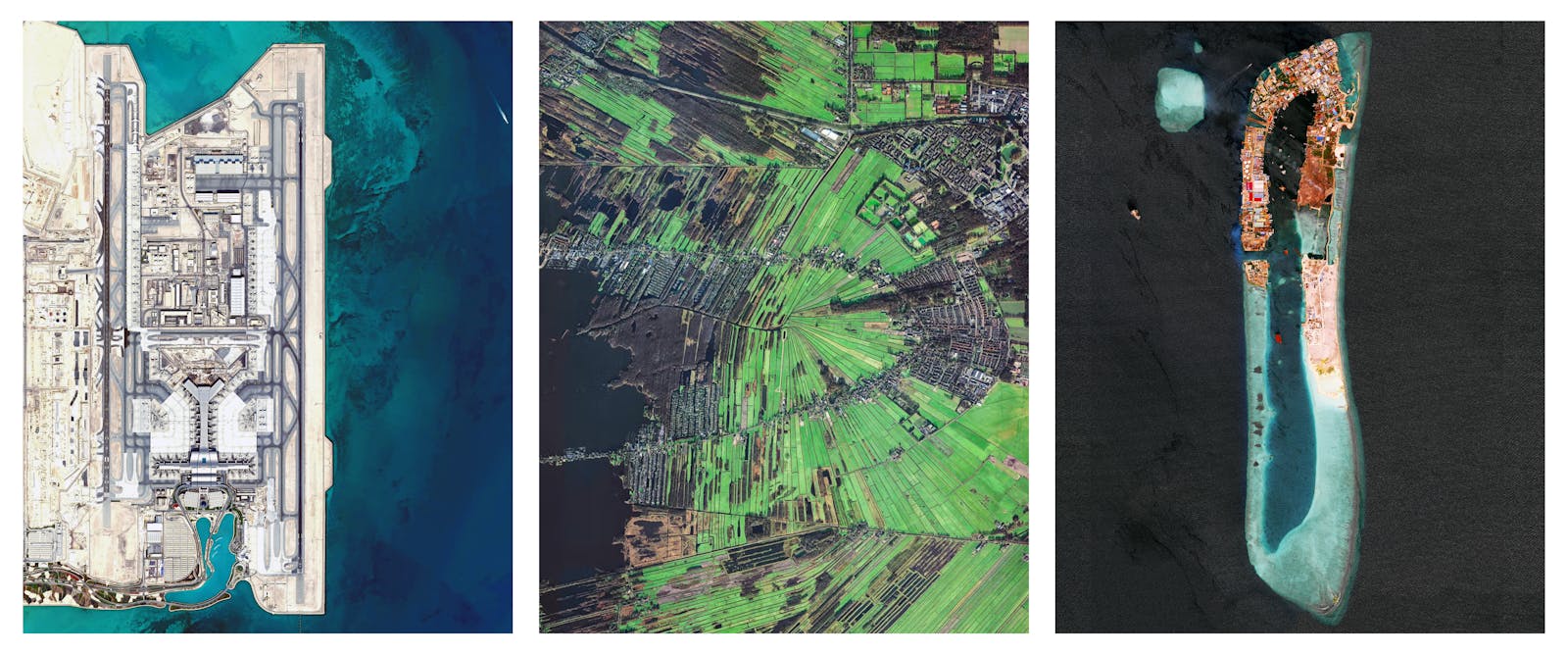

Land reclamation creates jobs, not only for those who do the actual reclamation work, but also for those who become employed at establishments on the added land. It can boost industry, tourism and overall economic development. The island city-state of Singapore is a prime example of this. It has used reclaimed land to build Changi Airport — one of the world’s busiest passenger airports — and Marina Bay, an 890-acre (360-hectare) extension to its Central Business District that contains some of the most valuable resorts in the world. Singapore is the smallest country in Asia, yet has one of the world’s most competitive economies thanks in large part to its land reclamation.